Image

The U.S. Capitol and the White House are symbols of democracy and the seat of power in the United States. However, they have also been the scenes of violence and bloodshed throughout the nation's history. From the War of 1812 to the present day, these buildings have witnessed attacks by foreign enemies, domestic terrorists, and even members of Congress themselves.

One of the earliest and most devastating attacks on the U.S. Capitol and the White House occurred during the War of 1812, a conflict between the United States and the British Empire over trade, territorial expansion, and impressment of American sailors. In 1814, a year into the war, American troops set fire to a capital in colonial Canada. In retaliation, British troops invaded Washington, D.C. and burned several federal buildings, including the White House and the Capitol. The fire did not completely destroy the buildings, but it damaged them severely and forced Congress to relocate temporarily. Some members of Congress even suggested moving the federal government back to Philadelphia or another city, but ultimately decided to rebuild and expand the Capitol and the White House.

The decades leading up to the Civil War were marked by intense political and sectional divisions, especially over the issue of slavery. These divisions often erupted into violence in Congress, where pro-slavery and anti-slavery representatives clashed verbally and physically. According to Yale history professor Joanne B. Freeman, there were more than 70 violent incidents between congressmen in the antebellum period, ranging from fistfights and stabbings to duels and canings. Congressmen during this period commonly carried pistols or bowie knives when they stepped onto the congressional floor, and some constituents even sent their congressmen guns.

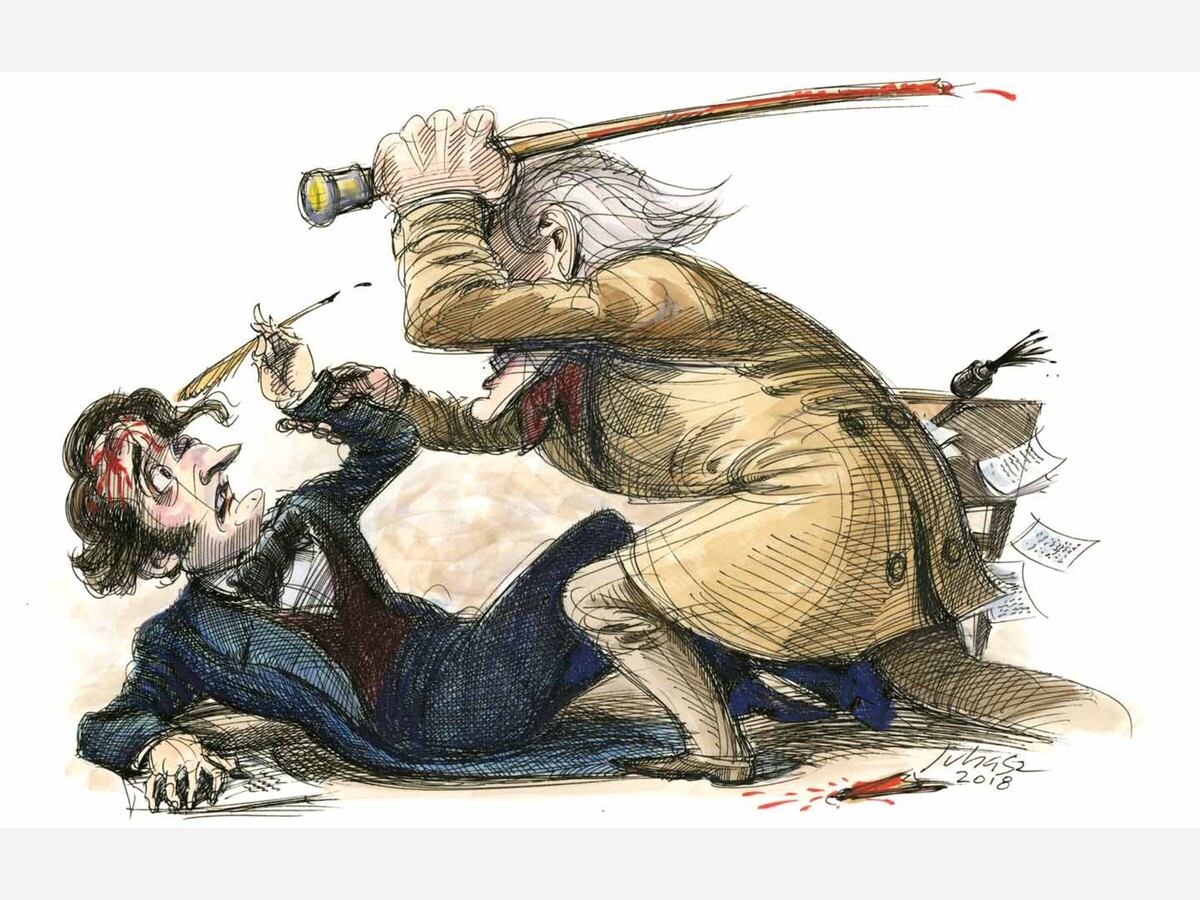

One of the most notorious examples of congressional violence was the caning of Charles Sumner, an abolitionist senator from Massachusetts, by Preston Brooks, a pro-slavery representative from South Carolina, in 1856. Brooks attacked Sumner on the Senate floor after Sumner delivered an anti-slavery speech that insulted Brooks' relative, Senator Andrew Butler. Brooks beat Sumner with a cane until he was unconscious, while other senators watched or tried to intervene. Sumner suffered severe injuries and took three years to recover, while Brooks became a hero in the South and received dozens of replacement canes from his supporters.

Another tragic example of congressional violence was the murder of Jonathan Cilley, a Democratic representative from Maine, by William Graves, a Whig representative from Kentucky, in 1838. Cilley and Graves did not have any personal animosity, but they were drawn into a duel over a political dispute involving a newspaper editor. Cilley refused to accept a letter from the editor, who had a reputation for physically attacking congressmen, and Graves felt obliged to challenge Cilley to a duel to defend his honor and that of his party. The duel took place in Maryland, where dueling was illegal, and lasted for three rounds. In the third round, Graves fatally shot Cilley in the chest, becoming the only congressman to ever kill another congressman.

The Civil War, the deadliest war in American history, pitted the Union against the Confederate states over the issue of slavery and states' rights. The war ended in 1865 with the surrender of the Confederate army and the abolition of slavery, but not before claiming the lives of more than 600,000 soldiers and civilians. Among the casualties of the war was President Abraham Lincoln, who was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer and actor, on April 14, 1865, just five days after the war ended. Booth shot Lincoln in the back of the head while he was attending a play at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. Lincoln died the next morning at a boarding house across the street from the theatre, becoming the first president to be assassinated.

Booth's assassination of Lincoln was part of a larger conspiracy to kill several members of the U.S. government, including Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William Seward. Booth's co-conspirators failed to carry out their plans, except for Lewis Powell, who stabbed Seward in his home, but did not kill him. Booth escaped from the theatre, but was tracked down and killed by federal troops 12 days later at a farm in Virginia. His co-conspirators were captured, tried, and executed or imprisoned.

The 20th century saw the rise of domestic terrorism in the United States, as various groups and individuals resorted to violence to advance their political, social, or religious agendas. Some of these attacks targeted the U.S. Capitol and the White House, either directly or indirectly. For example, in 1915, a German-born professor named Erich Muenter planted a bomb in the Senate reception room, hoping to stop the U.S. from entering World War I. The bomb exploded, but did not cause any casualties, as the Senate was not in session. Muenter then fled to New York, where he shot and wounded J.P. Morgan Jr., a prominent banker and financier. He was arrested and committed suicide in his jail cell.

In 1954, four Puerto Rican nationalists opened fire in the House of Representatives, wounding five congressmen. They were protesting the U.S. control of Puerto Rico and demanding its independence. They were arrested and sentenced to long prison terms, but were later pardoned by President Jimmy Carter in 1979. In 1971, a radical left-wing group called the Weather Underground bombed the Capitol, causing minor damage, but no injuries. They were protesting the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War and other issues. They claimed responsibility for the bombing in a letter, but were never caught.

In 1983, a group of anti-government extremists called the Armed Resistance Unit bombed the Capitol, causing more damage, but again, no injuries. They were protesting the U.S. intervention in Grenada and Lebanon. They also claimed responsibility for the bombing in a letter, but were not identified until 1988, when several members were arrested for other crimes. In 1994, a man named Francisco Duran fired more than two dozen shots at the White House, hitting the building, but not injuring anyone. He was apparently trying to kill President Bill Clinton, who was not in the building at the time. He was arrested and sentenced to 40 years in prison.

The 21st century has witnessed the emergence of new threats to the U.S. Capitol and the White House, mainly from foreign enemies and terrorist organizations. The most devastating attack occurred on September 11, 2001, when al-Qaeda, a radical Islamist group, hijacked four commercial airplanes and crashed them into the World Trade Center in New York, the Pentagon in Virginia, and a field in Pennsylvania, killing nearly 3,000 people and injuring more than 6,000. The fourth plane, Flight 93, was believed to be heading toward the Capitol or the White House, but was diverted by the passengers and crew, who fought back against the hijackers and sacrificed their lives.

Since then, the U.S. Capitol and the White House have been under heightened security and surveillance, but have still faced several attempts of attack or intrusion. For example, in 2009, a couple named Tareq and Michaele Salahi crashed a state dinner at the White House, posing as guests and mingling with President Barack Obama and other dignitaries. They were not armed or dangerous, but exposed a major security breach. In 2011, a man named Oscar Ortega-Hernandez fired several shots at the White House, hitting a window, but not injuring anyone. He was apparently obsessed with Obama and believed he was the Antichrist. He was arrested and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

In 2013, a woman named Miriam Carey drove her car into a security barrier near the White House, then led the police on a high-speed chase to the Capitol, where she was shot and killed. She was suffering from postpartum depression and psychosis, and believed Obama was communicating with her. In 2014, a man named Omar Gonzalez jumped the fence and ran into the White House, carrying a knife. He was tackled by a Secret Service agent and arrested. He had a history of mental illness and claimed he wanted to warn Obama about the atmosphere collapsing. In 2015, a man named Gyrocopter Man flew a small aircraft onto the Capitol lawn, carrying letters to Congress. He was protesting the influence of money in politics and wanted to deliver a message of reform. He was arrested and sentenced to four months in prison.

The U.S. Capitol and the White House are not only the centers of government, but also the targets of violence. Throughout the nation's history, they have been attacked by foreign enemies, domestic terrorists, and even members of Congress themselves. These attacks have resulted in death, injury, and damage, but have also inspired resilience, courage, and unity. The U.S. Capitol and the White House remain the symbols of democracy and the seat of power in the United States, but also the scenes of violence and bloodshed. Image sourced from Smithsonian Magazine online.